When Mari Strachan was a little girl, she used to create pretend newspapers, carefully writing the stories in pencil, drawing a picture to go with them, and then sewing the pages together. She says, “I’ve always loved the physicality of books and paper and writing instruments…”

When Mari Strachan was a little girl, she used to create pretend newspapers, carefully writing the stories in pencil, drawing a picture to go with them, and then sewing the pages together. She says, “I’ve always loved the physicality of books and paper and writing instruments…”

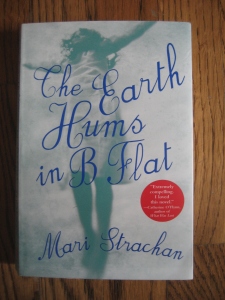

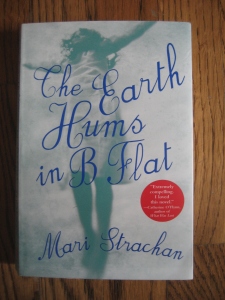

Now she is 64 years old, and has just published her first novel, The Earth Hums in B Flat. Her first novel! Congratulations, Mari!

Mari Strachan is Welsh. She lives part of the time in Wales and part of the time in London. As early as she can remember, she has loved books and reading and words, so it makes sense that she grew up to be a librarian, a book reviewer, a researcher, a translator, a copy editor, and a web editor. And now an author.

In The Earth Hums In B Flat, the main character is 12 1/2-year-old, Gwenni Morgan. Strachan reveals Gwenni’s personality in the way Gwenni interacts with objects in the world around her.

For example, early in the novel, imaginative Gwenni sees faces in the distemper [a kind of paint] in the scullery:

“The green distemper on the walls is beginning to peel and flake, shaping faces with sly eyes and mouths tight with secrets. There are new faces there every day.” (page 6)

Gwenni is, in fact, surrounded by people with secrets. Strachan pulls this thread through the novel.

“They’re not watching me this morning. They’ve closed their eyes and grown long ears so that they can listen…” (page 43)

She uses the faces to show Gwenni’s emotions:

“You scared the faces in the distemper, Mam.” (page 92)

“Will the faces open their mouths to scream out our secrets as the new distemper washes over them like a wave and drowns them?” (page 93)

It’s Gwenni’s relationship with the world around her that makes her such a compelling character. For more on this novel, please check out my review in the summer issue of Contrary Magazine as well as this interview with Mari Strachan at The View From Here Magazine, in which Strachan talks about where she writes, the difference between drafting and writing, and her favorite words.

I am caught in before and after time. Last-time things and firsts. (8)

I am caught in before and after time. Last-time things and firsts. (8)

The new issue of

The new issue of

You must be logged in to post a comment.